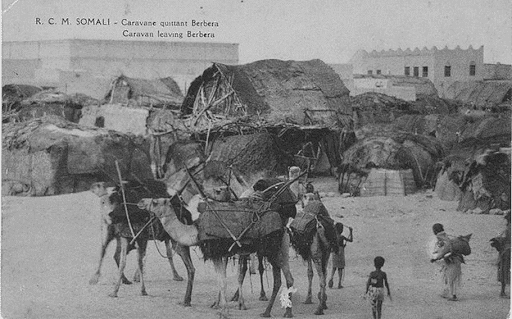

Across Somalia’s endless deserts, a camel caravan plods along, its shape silhouetted against a horizon that once marked the boundary of ancient empires. Thousands of kilometers above, an Airbus soars, connecting Mogadishu to Istanbul, Dubai and beyond. The contrast is stark—hooves in the sand and jet engines roaring—perfectly capturing Somalia’s transport journey. From the incense routes of the past to ride-hailing apps of today, Somalia’s story is one of resilience, adaptation and reinvention.

Somalia’s nomadic clans had mastered the art of traversing the Horn of Africa long before the invention of the wheel. Camels, called the “ships of the desert,” were more than just beasts of burden—they were the rhythm of trade, survival and identity. Somali poets through gabay verses immortalized their strength and endurance. The 19th century poet Raage Ugaas put it thus:

“In the red light of morning, there is glory in your eyes,

O you who ennoble with your presence.”

The camel was more than an animal to the Somali people—it was a symbol of wealth, sustenance and poetry in motion. The Somali people’s resilience was reflected in the very animals they relied on—carrying them not just across deserts but through the pages of history.

By the 1st century AD, trade had already turned Somali ports like Mossylon and Avalites into major commercial centers. Historians link Mossylon to today’s Bosaso and Avalites to modern-day Maydh in Somaliland as documented in The Periplus of the Erythraean Sea. These bustling ports attracted Greek and Roman merchants looking for frankincense, myrrh and exotic spices. At the same time Somali sailors commanded the Indian Ocean, navigating beden ships—swift wooden vessels that later influenced the design of Arab dhows.

Further down the coast, Zeila—also Seylac—became a major trading hub in northwestern Somaliland. Situated on the Gulf of Aden near today’s Djibouti, it was important for regional and international trade. The 14th century traveler Ibn Battuta described it as “a big city with big markets,” where caravans from far and wide came to trade gold, ivory and salt.

The 19th century saw foreign powers vying for control of Somalia’s coastline. The British upgraded Berbera’s port to service steamships, while the Italians built railways into the interior. Mogadishu–Villaggio Duca degli Abruzzi Railway was a railway line in southern Somalia that connected the capital city of Mogadishu to Villaggio Duca degli Abruzzi, now known as Jowhar. This line was completed in 1928, a symbol of colonial ambition – 114 km of track to funnel bananas, cotton and sugarcane to European markets. The line was dismantled by British troops during World War II. The focus on resource extraction led to the seizure of fertile lands and the establishment of large plantations which trespassed upon grazing areas vital for nomadic herders. This trespassing not only reduced the available pasturelands but also restricted access to water sources, thereby disrupting the delicate balance of nomadic pastoralism.

These infrastructure projects served colonial economic interests rather than local Somali communities. The new routes often cut across traditional nomadic paths, affecting the long established migration patterns of pastoral communities.

At independence in 1960, Somalia’s leaders had a vision for a modern country. Mogadishu International Airport, opened in the 1960s with a runway long enough for jets, was a symbol of progress. Soviet engineers built the 1,000 km Mogadishu-Hargeisa Road, while US funded the modernization of the Port of Kismayo.

This marked a significant period of development for Somalia, particularly in aviation, when Asli Hassan Abade made history—not just for her country but for the entire African continent. In 1976, she became Africa’s first female military pilot, breaking long-standing gender barriers in a traditionally male-dominated institution. As Somalia’s first female pilot, she flew a Cessna before transitioning to military aircraft for the Somali Air Force. This was the high point of development for Somalia, in aviation in particular where Asli Hassan Abade was making history not just for Somalia but for the whole continent.

Civil war in 1991 destroyed Somalia’s transport infrastructure. Roads crumbled, airports were abandoned and railways rusted away. But in the midst of chaos, inventiveness flourished. The Alula truckers – named after the resilient coastal town of Alula (Caluula) a coastal town located in Puntland, Somalia – local truck drivers from coastal towns like Alula became unsung heroes, navigating by stars through treacherous and often unmarked roads to deliver essentials.

The sky’s the limit. Today Aden Adde International Airport, once a war torn airstrip, now has international flights from Turkish Airlines and Ethiopian Airways. Local airlines are also expanding their reach, including Salaam Air Express, which connects Mogadishu with regional and international destinations, providing a crucial link for trade and travel. UAE funded upgrades to Berbera Port aims to position Somaliland as a Red Sea trade hub, Turkish companies are revamping Mogadishu’s urban roads. Even the camel, now equipped with GPS trackers, is still essential for rural communities adapting to droughts caused by climate change.

Somalia’s journey is one of endurance and transformation. From camel caravans tracing ancient trade routes to modern aircraft linking cities, the nation has always moved forward. With every rebuilt road and flight from Aden Adde International Airport, Somalia embraces both heritage and progress. As the desert wind whispers of the past and jet engines carve new paths above, the country continues its journey—where tradition and innovation walk side by side. As a Somali proverb says, “Haddaad rabtid in aad guulaysatid, raadadka kuwii hore mari”—”If you want to succeed, follow in the footsteps of those who came before.”

African Development Bank. (2023). Somalia Infrastructure Fund: Annual Progress Report 2023. Retrieved from https://www.afdb.org/en/documents/sif-annual-progress-report-2023

Battuta, I. (2002). The Travels of Ibn Battuta: A Translation (R. B. Serjeant, Trans.). London: Routledge.

Chittick, N. (1980). Sewn boats in the western Indian Ocean, and a survival in Somalia. International Journal of Nautical Archaeology, 9(1), 73–76.

Huntingford, G. W. B. (1980). The Periplus of the Erythraean Sea: With Some Extracts from Agatharkhidēs ‘On the Erythraean Sea’. Hakluyt Society.

Hiiraan Online. (2021). If the camel is fine, our life is fine – but Somali camel herding is in jeopardy. Retrieved from https://www.hiiraan.com/news4/2021/May/182668/_if_the_camel_is_fine_our_life_is_fine_but_somali_camel_herding_is_in_jeopardy.aspx

Lewis, I. M. (2002). A Modern History of the Somali: Nation and State in the Horn of Africa (4th ed.). Ohio University Press.

Turkish-Somali Infrastructure Developments. (2022). Mogadishu’s Rebuilding Efforts and Infrastructure Investment. Retrieved from https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Turkey%E2%80%93Somalia_relations

Salaam Air Express offers fast, safe, and reliable air transport services across East Africa, with a focus on exceptional customer experiences. Explore the Pristine Beauty of Africa with Us!

Gasimiya Bldng, KM4, Hodan, Mogadishu

+252 617 218 811 |

+252 616 999 964

Wilson Airport, Lengai House, 1st Floor

+254 740 666 066

Jomo Kenyatta International Airport, T2

+254 717 294 447

Eastleigh, Istanbul Mall, 3rd Flr, Nairobi

+254 794 227 384 |

+254 707 800 900

D&L Bldng, 1st Floor, Unimiss Road, next to Airport Gate Exit, Juba

+211 915 629 668 |

+211 919 900 835